-

Stanford’s Dam Dilemma

- Posted on 15th Feb

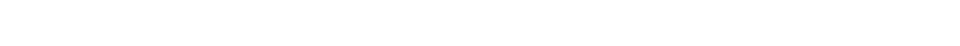

- Category: DamNation

Hidden behind the fences of Stanford’s Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve, Searsville Dam creates a stagnant reservoir where algae and non-native species thrive while steelhead and other threatened species are trapped downstream.

Matt Stoecker spent his childhood tromping around in the creeks of the San Franciquito watershed where he grew up, hunting for frogs, fishing and exploring.

One day in the mid-90s, he found himself below the 65-foot-tall Searsville Dam on the Corte Madera Creek when he experienced a seminal moment: He saw a 30-inch steelhead jump out of the water and smash itself against the dam.

He had never seen a fish that size in the creek, and he was struck at the power and futility he witnessed.

Stoecker soon began volunteering with the San Francisquito Watershed Council, then started a steelhead task force and has been working to remove small dams and other fish barriers in the watershed ever since.

But all along, he said, “Searsville Dam was the biggest limiting factor.”

The dam, which is owned by Stanford University, was recently pushed into the spotlight because of a major sedimentation problem in the reservoir, a large-scale study of the dam, a federal investigation into possible violations of the Endangered Species Act and a lawsuit against Stanford.

While university officials argue that dismantling the dam could jeopardize the reservoir’s riparian ecosystems and threaten downstream communities, Stoecker and other environmentalists say it’s been blocking fish passage for too long and it’s time for the dam to come down.

“It’s an antiquated, environmentally harmful reservoir that’s at the end of its useful life,” Stoecker said.

Searsville Dam and Reservoir sit amid the oak stands and serpentine grasslands of the Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve, a 1,189-acre outdoor laboratory used by Stanford University for research and education. The reservoir, which was created by the damming of Corte Madera Creek in 1892, was acquired by Stanford in 1919. Today it serves to store non-potable water for landscape irrigation at the school.

San Francisquito Creek contains one of the last wild steelhead runs in the South San Francisco Bay, but Searsville Dam directly blocks their annual migration upstream to approximately 20 miles of former spawning and rearing habitat.

But over the years, the reservoir has filled with an estimated 1.5 million cubic yards of silts, gravels and woody debris that have cost it more than 90 percent of its original capacity. Some experts estimate that the reservoir could fill entirely within a decade. Along with loss of the reservoir, sedimentation behind the dam threatens surrounding communities with possible flooding.

The sedimentation issue helped prompt Stanford to form a 12-person steering committee in 2011 to study its options. The study is examining such things as Stanford’s long-term water needs, fish passage, flood risks, the costs of dredging and the impact on university research programs.

According to Stanford, expert consultants are studying a number of options, including dredging, allowing the reservoir to continue to fill and transition to a marsh, modifying the dam and removing the dam altogether.

“From my perspective, the overall goal is to figure out what is the best, most responsible way to manage this watershed,” said Chris Field, faculty director of Jasper Ridge and professor of biology and of environmental Earth system science, who co-chairs the steering committee. “It’s a lot to learn and, at least for me, it’s important that we do a really good, thorough job … My feeling is that these issues are ones that have taken decades to build up, and we want to make sure any course of action we recommend is thought through deeply and also recognizes all the stakeholders.”

Complicating the issue is the role the reservoir plays in the preserve.

The reservoir, Field said, is home to beautiful open water and wetland habitats used by a large number of nesting and migratory birds. It sustains habitats for diverse plants and animals, including bats, salamanders and fish. It has also served the university as a living classroom for many years.

Despite that, Field said, the university “doesn’t have a preset goal of preserving the lake.”

Stanford anticipates completing the initial set of studies and recommendations in 2014. Its president and provost will ultimately decide how to act on them.

Stoecker, who is now a biologist, had been pushing for a deeper look at Searsville Dam long before the school initiated its study.

In 1999 he helped start a steelhead task force for the San Francisquito Watershed Council, which identified Searsville as the biggest barrier to migrating steelhead in the watershed, a primary source of non-native species and a principle contributor to the degradation of habitat. In 2001, along with Stanford and others, he helped form the Searsville Dam Working Group. It got the California Department of Water Resources to offer to fund an analysis of options for the dam — an offer Stanford declined.

“Since then, every time we tried to bring up finding a Searsville solution that worked for everyone, folks from Stanford didn’t want to talk about it,” Stoecker said.

In 2008, Stoecker formed Beyond Searsville Dam in partnership with American Rivers to push for a serious consideration of dam removal.

Searsville Dam was built by the Spring Valley Water Company to supply drinking water to residents of the San Francisco Peninsula, but it never did. Instead, Stoecker said, for more than a century it has impeded fish passage to historic habitat, dewatered downstream creeks and blocked the transport of gravels, woody debris and sediment that is vital to a healthy river system and the San Francisco Bay. The reservoir flooded and buried a valley where several streams once merged among wetlands and riparian forests, and has created an artificial habitat for non-native and invasive species.

Native rainbow trout (descendants of sea-run steelhead) persist in creeks upstream of Searsville, but are at risk of being wiped out due to inbreeding caused by the impassable dam and lack of returning steelhead to maintain genetic diversity.

“Each year as it fills in more and more, it becomes less useful, more problematic and more expensive to fix,” Stoecker said, adding that Searsville provides a small amount of water to the university, which has plenty of options for water storage that do not imperil wildlife.

“There are definitely better and less harmful ways of getting water and eliminating the need for this dam,” he said. “Based on other projects that have happened or are under way, and on studies from our nation’s top scientists, dam removal and low-impact water supply upgrades are preferable in terms of benefit to the ecosystem, surrounding communities and Stanford.”

Steve Rothert, California director of American Rivers, who also grew up upstream of the dam, said Stanford has “time and again missed opportunities to take initiative and take a leadership role in this.

“I think Stanford has a phenomenal opportunity to create another broad set of studies that would be associated with the changes that would take place with removal of the dam and recovery of the natural ecosystem,” he said.

Rothert said he is encouraged by Stanford’s current study, and thinks the committee consists of capable and committed people. But, he said, the fate of the reservoir is ultimately up to university officials, not steering committee members, and the university has appeared reluctant to open up the process.

For Rothert, the study would ideally lead to a project that provides fish with unhindered access to the upper basin, the safe transport of sediment and wood and water downstream, and provides Stanford with the opportunity “to regain a principled posture on this issue that is consistent with its image as a leader in science.”

In January, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) announced it is investigating whether Stanford is violating the Endangered Species Act (ESA) through its operation of Searsville Dam. Steelhead in this watershed are considered “threatened,” and as such, have been protected since 1997 under the ESA. (A “take” is an action that kills, harms or harasses a threatened or endangered species.)

Following that news, two environmental groups — Our Children’s Earth Foundation and the Ecological Rights Foundation — filed a suit against the university alleging it is violating the ESA for harming steelhead trout.

Stanford officials have expressed confidence that the school has not violated the act.

“The university believes that it is in full compliance with the Endangered Species Act and all local, state and federal laws in its operations of Searsville Dam and Reservoir,” states a FAQ put together by Stanford.

But Stoecker and Rothert, along with their legal team, disagree.

“There are clear impacts on the fish from blocked passage to dewatered habitat that we think constitute a violation of the ESA,” Rothert said. “We think the situation definitely warrants an investigation.”

By Katie Klingsporn

About the Author

Katie Klingsporn is a writer and editor of the Telluride Daily Planet in southwestern Colorado. Look for more of her posts highlighting issues featured in DamNation a documentary film being produced by Patagonia and Stoecker Productions in conjunction with the Colorado-based filmmaking team Felt Soul Media. -

A River Reestablishes Itself

- Posted on 28th Dec

- Category: DamNation

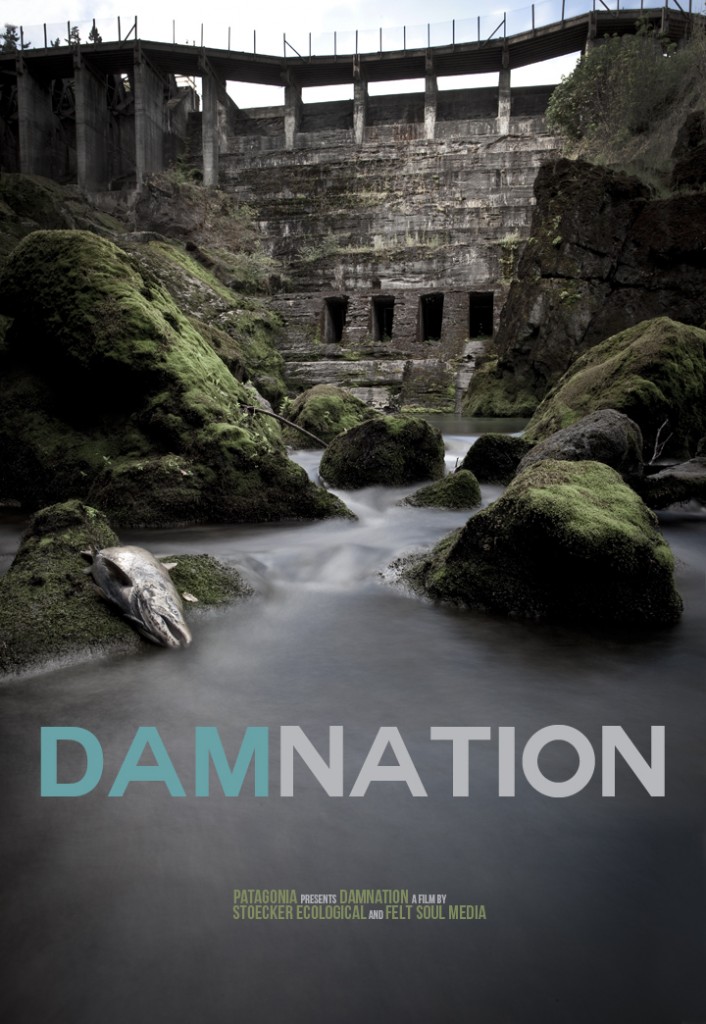

The 210 foot Glines Canyon Dam in Olympic National Park has illegally blocked spawning habitat for an extraordinary chinook salmon run since 1927. Photo by Ben Knight/DamNation

In September of 2011, machines began chipping away at the Elwha Dam in Washington’s lush Olympic Peninsula, kicking off the largest dam-removal project in United States history.

The dam has since been completely removed from the section of the Elwha River it had occupied since 1913. Another dam upstream, the Glines Canyon Dam, located in Olympic National Park, is partially dismantled and expected to be a thing of the past by early next summer, freeing the river for the first time in 100 years.

The landmark project is the culmination of a costly, multi-year river-recovery effort put together by the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and a coalition of state and federal entities. The idea is to reconnect a severed river, one in which the hundreds of thousands of adult salmon that used to spawn each year have dwindled to a few thousand.

But while it represents an impressive set of partnerships and a noble cause, it is also a grand experiment. Dam removal of this scale has never been done in the U.S. And with a staggering 24 million cubic yards of sediment being released into the river, there were some doubts about the project’s success.

So far, though, it’s been a promising story of recovery.

Within weeks of the Elwha coming down, fish were observed moving beyond the site of the former dam. Recolonizing adult coho salmon and wild winter steelhead reached well beyond within seven months. And in August, adult chinook salmon were seen in the park — the first observed salmon to naturally migrate into the watershed.

“So far it’s been good,” George Pess, a scientist with NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center who has been working on the Elwha for years, said this fall. “I think things have worked out pretty well. The fish have responded favorably.”

Biologists this winter have been keeping a close eye on the coho and chum salmon expected to migrate upstream to spawn during the fish window of November and December. Although turbidity is high in the river — due in part to increased rainfall — up to 5,000 coho and chum could make their way upstream, according to the Park Service.

Meanwhile, the high stream-flow and heavy turbidity have been transporting a great deal of sediment down the river, which is causing dramatic changes as it fills in pools, creates new beaches and reshapes the river.

Recovery isn’t limited to the river channel. Biologists have been replanting a forest of new vegetation along the banks of the river and at the sites of the two reservoirs that once sat above the dams. And the transportation of nutrients that salmon bring to an ecosystem has begun.

As the Elwha Dam was removed its reservoir receded, revealing beautifully preserved old growth cedar stumps and sites of cultural signifigance to the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe. Photo by Ben Knight/DamNation

Another noteworthy piece of the project, said Barb Maynes, a public affairs officer for Olympic National Park, is cultural recovery. In August, members of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe gathered at their people’s sacred creation site — long buried by the waters of one of the reservoirs — for the first time in 100 years.

“It’s been a really exciting year since dam removal started,” Maynes said.

Dylan Tomine, a Patagonia fly-fishing ambassador, author and Wild Steelhead Coalition trustee, noted that the Elwha provides an excellent opportunity to test post-dam river recovery because it’s in pristine habitat.“I think it’s really just an incredibly interesting laboratory to see how nature responds to this kind of thing,” Tomine said.

Right now, Tomine said, the Elwha’s not the prettiest place in the world. The water is loaded with sediment and what once were reservoirs are now dry lakebeds.

“But it’s been very encouraging,” he added. “To be able to see the river carving its own path again, without sounding too sappy, it’s a pretty moving thing.”

The only fly in the ointment for Tomine is the presence of a hatchery on the river; he would rather see fish returning naturally. But overall, he says it holds a great deal of promise, demonstrating what can happen if people are committed enough to a cause.“The fact that we seem to be in an age of actually removing dams is pretty amazing,” Tomine said.

Workers are removing the Glines Canyon Dam gradually to allow the river to flush out sediment over time. Downward notching is on hold until January for the winter fish window.

Before the dams were built — the Elwha in 1913, and the Glines Canyon in 1927 — an estimated 400,000 adult salmon swam up the Elwha River each year to spawn, including monster Chinook that weighed up to 100 pounds. Steelhead and trout populations were also robust.

Annual salmon populations have dwindled to just a few thousand, but the Park Service is hoping their numbers return to historic proportions in the coming decades.

Tomine is optimistic.

“I think we’re going to see the project being completed and the river returning to its natural state. It’s really an example of people working together and really sticking to it,” he said.

By Katie Klingsporn

About the Author

Katie Klingsporn is a writer and editor of the Telluride Daily Planet in southwestern Colorado. Look for more of her posts highlighting issues featured in DamNation a documentary film being produced by Patagonia and Stoecker Productions in conjunction with the Colorado-based filmmaking team Felt Soul Media. -

America: the DamNation

- Posted on 24th Oct

- Category: DamNation

Executive Producer of DamNation and Patagonia founder, Yvon Chouinard, has long been an advocate of dam busting and protecting free flowing rivers. Photo by Tim Davis.

Despite their imposing numbers and size, most people never give dams a second thought.

Patagonia founder and owner Yvon Chouinard is not one of those people.

When he sees dams, he sees broken waterways, an antiquated way of thinking and a means of generating energy that is far from green. He also sees the potential to mend the damage by taking down dams.

“I’m a fisherman, and I want to see fish come back to these rivers,” Chouinard said. “I want to establish that when you put in a dam or when you dig an open-pit mine or scrape down a mountain, that you have to restore it. There’s a public trust there and you have to restore it.”

Chouinard [...] and biologist Matt Stoecker, are at the forefront of a growing movement to decommission dams in America. The best way to do that, they figure, is by raising public awareness and support. And they believe the public will only support dam removal if they understand the complexities.

That’s the idea behind DamNation, a feature documentary produced by Patagonia and Stoecker Ecological in conjunction with the Colorado-based filmmaking team Felt Soul Media.

The film, which will be released in spring 2013, explores successful dam-removals, looks at dams that are subject of current removal fights and shines a light on others eyed for future dismantling. It paints the history of dam building in America, and chronicles the evolution of dam-busters from the radical monkey-wrenchers of yore to the tie-wearing coalition-builders of today. It focuses on some of the pivotal figures on either side of the dam issue.

Shooting began last summer, with filmmakers Ben Knight, Travis Rummel and Stoecker gathering footage from Maine to California.

Matt Stoecker, DamNation’s co-producer and underwater cinematographer, takes a break above water while filming below the Elwha Dam before its removal. Photo by Ben Knight

Though Chouinard and Stoecker aren’t shy about their position on taking down dams,DamNation seeks to explore the issue fairly. The filmmakers interview the farmers who rely on dams to irrigate their fields, Native people whose cultures’ depend on the salmon that dams have destroyed, and legislators who view dam opponents as environmental extremists. They speak with scientists, dam employees and others.

“Our goal is to let the audience make up their own minds by giving them all sides of the issue,” Rummel said. “I don’t think it’s a black and white issue where it’s take out every dam.”

Despite their usefulness, dams have hugely impacted the rivers they were built in, and many have outlasted their purpose.

“I think the public is unaware of this,” said Chouinard. “I don’t think they realize that there’s a lifespan for these things.”

Chouinard has been working for two decades to take out dams, and he has discovered a pattern. Efforts typically begin with a small grassroots group that faces a steep uphill battle. Opponents are powerful, red tape is plentiful and many who are involved are resistant to change. If the group does manage to make it through the bureaucratic and permitting thickets and gain funding, support and success, it’s only through years of really hard work.

“But then the dam comes down and the river begins to almost instantaneously heal,” Chouinard said. “And then there’s not one person who says, ‘gee that was a mistake.’”

The impetus for DamNation came from the desire to mainstream dam removal by showing the many benefits that result. Stoecker, who worked to successfully remove his first dam 10 years ago, noted that while dam-busting used to be a fringe idea, it’s now one routinely considered by governments and dam owners, as well as environmentalists.

“Now we’ve got less harmful alternatives,” said Stoecker. “There’s been a total shift in thinking.”

A good example of this new mindset, he said, can be found on the Elwha River in Washington, where a coalition of Native tribes, environmental groups and government officials worked together to take out the biggest dams in U.S history — the Elwha and Glines Canyon dams in and near Olympic National Park (a project featured in the film).

“There are wild steelhead and salmon returning to the river above the Elwha Dam site before the project’s even done,” Stoecker said.

Chouinard hopes DamNation will open people’s eyes.

“I just hope it gets around to a lot of people and changes their way of thinking about dams,” he said. “I’d like to see a few more dams come down in my lifetime.”

By Katie Klingsporn

Katie Klingsporn is a writer and editor of the Telluride Daily Planet in southwestern Colorado. Look for more of her posts highlighting both the development of “DamNation” and the issues surrounding the complex topic of dam removal in America.

-

Used dams for sale, best offer

- Posted on 15th Aug

- Category: DamNation

We’ve heard of a non-profit raising money to save something, but have you ever heard of buying something to destroy it? Well, that’s the idea Laura Rose Day [left], executive director of the Penobscot River Restoration Trust put into action.

In December 2010, a group of organizations working together as the Penobscot River Restoration Trust officially took possession of the Veazie, Great Works and Howland dams from Pennsylvania Power and Light in a historic deal worth $24 million.

From Kevin Miller at the Bangor Daily News: Under an agreement brokered in 2004, PPL agreed to sell the three dams to the trust for roughly $25 million. PPL, in return, gained authorization to increase power generation at six other dams along the river, entirely offsetting the generation losses incurred when the Veazie, Howland and Great Works dams are decommissioned.

“This landmark partnership has proven that business, government and interested citizens can reach mutually agreeable solutions that benefit the community, the economy and the environment,” Dennis Murphy, a vice president and chief operating officer at PPL, said in a statement Monday.

Once complete, the project will have reopened nearly 1,000 miles of river and streams within the Penobscot watershed to endangered Atlantic salmon, sturgeon, American shad, alewives and seven other species of migratory, sea-run fish. In turn, those species help support other commercially important species, such as cod and lobster.

“This may well turn out to be the most important day for Atlantic salmon in the past 200 years,” Bill Taylor, president of the Atlantic Salmon Federation, said in a statement Monday. “The Penobscot project is our best — and perhaps last — chance of restoring a major run of wild Atlantic salmon in the United States.”

But supporters insist fish and other wildlife won’t be the only beneficiaries. They also predict that fishermen and tourists will be drawn to the freer-flowing river. The Penobscot endeavor has been hailed internationally as a model river restoration project. [Kevin Miller, Bangor Daily News]

Demolition of the Great Works Dam [pictured above with Laura Rose Day] is slated to begin in the summer of 2012. There’s a damn good chance it’ll be the biggest party Bangor Maine has ever thrown.

-

DamNation Q&A featured on Outside Magazine’s Adventure Ethics Blog

- Posted on 9th Jul

- Category: DamNation

Outside Magazine’s Adventure Ethics blog featured a Q&A with our producers Matt Stoecker and Travis Rummel. Huge thanks to Mary Catherine O’Conner for the thoughtful questions.

-

Title, check. Synopsis, check.

- Posted on 31st Mar

- Category: DamNation

Ok, two things: the above photo of Washington’s lower Elwha Dam was taken about six months ago. It is now GONE. Secondly, I had to look up the word “synopsis” which is probably a bad sign when you’re writing a synopsis. Oh well, don’t judge.

Ninety-nine years after Olympic National Park’s Elwha River was illegally dammed, wild Chinook salmon still instinctively gather at the foot of the lower dam as if they sense a change in the current. Upstream, the usual low rumble of antique turbines generating electricity has faded, and the piercing sound of an excavator-mounted jackhammer reverberates off the 210-foot tall Glines Canyon Dam. De-construction crews have begun the painstaking process of chipping away at its mossy, con-caved facade. This moment marks the beginning of the largest dam removal in US history, unveiling the best opportunity for wild salmon recovery in the country.

Dam removal is no longer the work of a fictional Monkey Wrench Gang. It’s real, upon us, a cornerstone of the modern environmental and cultural movements. The benefits from dams, including hydropower, urban water supply, irrigation, and flood protection have played a critical role in the development of the United States—but river ecosystems and Native American heritage suffered greatly. Now, many of these antiquated relics of the industrial revolution are classified as public safety hazards by the Army Corps of Engineers.

The short-sighted development of a bygone era is growing more prevalent—In many cases, the high cost of retrofitting an aging dam, and meeting current environmental standards has led to a surprising shift in thinking: Dam owners, impacted communities, and politicians are now reevaluating the usefulness of certain dams and often advocating for decommissioning and removal. Some call it a movement, others call it a generational shift in values. Regardless of what it’s dubbed, an undeniable momentum behind river restoration has begun.

DamNation is a collection of empassioned voices and spirited stories from the people entrenched on both sides of this devisive issue. Examining the history and controversy behind current and proposed dam removal projects, DamNation presents a dynamic perspective on Man’s attempt to harness and control the power of water at the expense of nature. Nothing lasts forever, not even the concrete monoliths that have impounded America’s free flowing rivers in the name of “progress” for ages.

—Ben Knight

-

On a divisive dam, a snippy bit of graffiti

- Posted on 6th Dec

- Category: DamNation

We really enjoyed this LA Times article by Steve Chawkins

We really enjoyed this LA Times article by Steve ChawkinsA huge scissors and a dotted line appear on a dam near Ojai. The message: Tear it down.

If life imitated art, it would be a simple matter to follow the dotted line and snip a 200-foot dam near Ojai off the face of the earth. For years, an alliance of environmentalists, fishermen, surfers and officials from every level of government has called for demolishing the obsolete structure. Now, an anonymous band of artists has weighed in, apparently rappelling down the dam’s face to paint a huge pair of scissors and a long dotted line. The carefully planned work popped up last week and is, no doubt, Ventura County’s most environmentally correct graffiti by a dam site.

“Everyone I’ve talked to has really enjoyed it,” said Jeff Pratt, Ventura County’s public works director. “It sends a good message.” That message? Tear the thing down already.

Matilija Dam was built in 1947 for flood control and water storage. But officials say it was flawed from the outset. For decades, it’s been holding back silt as much as water, depriving beaches 17 miles downstream of the sand they need to replenish themselves.It’s also been deemed a huge obstacle for steelhead trout, an endangered species that was once a trophy fish luring anglers from across the country.

Officials say they don’t know who painted the shears, and they’re careful to note that such acts — even in the name of art — are illegal and dangerous. The dam is challenging enough that rescue squads use it for climbing practice, pounding in metal anchors that may have aided the scissors hands. But even if the painting is no more legal than garden-variety graffiti, some say it speaks to the takedown’s glacial pace.

“We’ve studied this to death and talked about it forever,” said Paul Jenkin of the Matilija Coalition, an alliance of community groups pushing for the dam’s removal. “There’s very strong support from the community, and that’s part of what we’re seeing with the graffiti.”

Coincidentally, environmentalists, county officials, the Army Corps of Engineers and others concerned about Matilija met on Wednesday — the morning a story about the mystery shears appeared on the front page of the Ventura County Star. The group is facing obstacles comparable to those of the steelhead trout: six million cubic yards of silt, an earthquake fault, and costs estimated at more than $140 million. In better times, federal funding seemed close at hand — but now, not so much. The current plan is ambitious enough: Take pressure off the aging structure by chopping 20 feet off the top and allowing more sediment to wash downstream. Meanwhile, the artwork will stay in place. ”It’s certainly raised awareness,” Pratt said. [Steve Chawkins, LA Times, Sept. 19, 2011]

-

Sunbeam

- Posted on 6th Oct

- Category: DamNation

Thanks to a bit of inspiration from author Steven Hawley, we paid our respects to Idaho’s Sunbeam Dam on the Salmon River. Constructed in 1910 to provide power to a near-by mining operation, little thought was given to the fact that it blocked fish passage—most importantly to the Idaho sockeye. Today, about two thirds of the original structure remains—but the details of how it was breached in 1934 are surprisingly foggy. Idaho Fish and Game supposedly had a line item on the budget for demolition of the dam in 1930, but Hawley says it went unpaid. What’s left of the Sunbeam tombstone may be our earliest example of river restoration done right: blow the son-of-a-bitch up, and the river will take care of the rest.

-

Our boy – Matt Stoecker

- Posted on 5th Oct

- Category: DamNation

DamNation producer and career restoration ecologist Matt Stoecker emerges from the deep, cold, creepy currents of Elwha Dam’s river right spillway. We lent Matt our underwater housing and he’s been taking care of all our aquatic wildlife needs. The Chinook were a bit timid that day, but he was able to sneak up on a couple pinks doing unmentionable acts of fish love just a dozen yards downstream. Take a gander at this hot profile Chris Malloy and Jason Baffa put together on Matt for Patagonia’s “PreOCCUPATIONS” series:

Despite their imposing numbers and size, most people never give dams a second thought." width="350" height="233">

Despite their imposing numbers and size, most people never give dams a second thought." width="350" height="233">